Analysis of prognostic value of self-reported insomnia in patients with angina pectoris based on propensity score matching

-

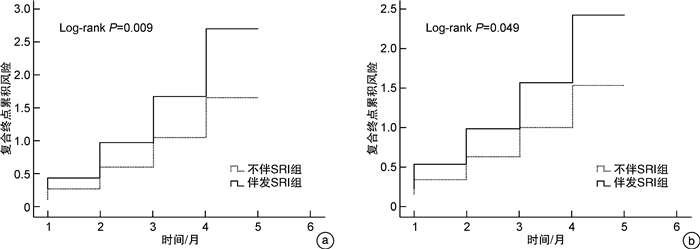

摘要: 目的调查冠心病心绞痛患者中自述失眠(SRI)的发病率,探讨SRI对心绞痛患者出院后6个月预后的预测价值。方法连续纳入2017年6月—2021年3月河北医科大学第一医院心内科住院的541例冠心病心绞痛患者,按是否发生SRI分为心绞痛伴SRI组和心绞痛不伴SRI组。以出院后6个月内的全因死亡、再发心绞痛入院、再次行冠状动脉(冠脉)介入治疗或移植手术、急性心力衰竭、脑卒中的复合事件为随访终点,应用倾向性得分匹配法(PSM)对2组患者基线数据进行匹配,通过Cox回归分析SRI对心绞痛患者的预后价值,并绘制累积风险曲线。结果入选的541例冠心病心绞痛患者中伴发SRI者189例(34.9%)。PSM前心绞痛伴发SRI组与不伴SRI组患者的年龄、男性比例、心率、血压、白细胞计数、肌酐、总胆固醇、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇、B型利钠肽、左心室射血分数和β受体阻滞剂应用比例有统计学差异;服用助睡眠药物患者比例和用药频率、匹兹堡睡眠指数(PSQI)评分均差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05);Cox多因素分析结果显示,SRI组患者6个月内复合事件风险增加85.2%(HR=1.852,95%CI:11.223~2.478,P=0.039)。经PSM后,共有187对患者匹配成功,各协变量达到平衡,SRI仍为心绞痛患者6个月内不良预后的独立预测因子,校正混杂因素后复合事件风险增加50.3%(HR=1.503,95%CI:1.247~1.811,P=0.042)。结论冠心病心绞痛中SRI的发生率为34.9%,SRI对心绞痛患者的6个月不良预后具有独立的预测价值。Abstract: ObjectiveTo investigate the incidence of self-reported insomnia(SRI) in patients with angina pectoris and to explore the predictive value of SRI on the prognosis of patients with angina pectoris 6 months after discharge.MethodsA total of 541 patients with angina pectoris, who were hospitalized in the First Hospital of Hebei Medical University from June 2017 to March 2021, were enrolled. According to the occurrence of SRI, they were divided into angina pectoris with SRI group and angina pectoris without SRI group. The primary end point was the composite of all-cause death, recurrent angina pectoris, coronary intervention or bypass surgery, acute heart failure, or stroke during 6 months after discharge. Propensity score matching(PSM) was applied to match the baseline data of patients in the 2 groups and the cumulative risk curve was plotted.ResultsAmong 541 patients, 189 comorbid with SRI, and the incidence of SRI was 34.9%. Before PSM, the age, male ratio, heart rate, blood pressure, white blood cells, creatinine, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, brain natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction, and the proportion of beta blockers used in the patients with and without SRI groups were different singnificantly; the number and frequency of sleep aids, and the scores of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index(PSQI) were statistically significant(P < 0.05). Cox multivariate analysis showed that the risk of composite events within 6 months increased by 85.2%(HR=1.852, 95%CI: 11.223-2.478, P=0.039) in the SRI group. After PSM, 187 pairs of patients were successfully matched and the covariates were balanced. The SRI remained an independent predictor of adverse outcomes for 6 months in angina patients, with an increased risk of 50.3% after adjusting for confounders(HR=1.503, 95%CI: 1.247-1.811, P=0.042).ConclusionThe incidence of SRI in angina pectoris of coronary heart disease is 34.9% and SRI has independent predictive value for poor prognosis in angina pectoris patients 6 months after discharge.

-

Key words:

- self-reported insomnia /

- angina pectoris /

- prognosis /

- propensity score matching

-

-

表 1 2组患者PSM前的临床基线数据比较

Table 1. General data before PSM

例(%), X±S, M(P25, P75) 项目 心绞痛伴SRI组(189例) 心绞痛不伴SRI组(352例) t/Z/χ2值 P值 年龄/岁 67.8 ± 14.1 64.8 ± 13.2 2.421 0.016 男性 83(43.9) 187(53.1) 4.172 0.041 吸烟 65(34.4) 124(35.2) 0.038 0.846 BMI/(kg·m-2) 25.8(22.9,28.1) 25.2(22.9,27.6) -1.337 0.136 入院时心率/(次·min-1) 89±22 84±23 2.447 0.015 入院时收缩压/mmHg 137±16 134±17 1.997 0.046 伴随疾病 高血压 59(30.7) 96(27.3) 0.936 0.333 糖尿病 50(26.5) 91(25.9) 0.023 0.879 脑卒中 32(16.9) 54(15.3) 0.233 0.630 白细胞计数/(×109·L-1) 8.11(5.69,11.04) 7.25(5.46,9.10) -2.119 0.034 肌酐/(μmol·L-1) 84.7(69.5,106.3) 85.6(67.8,105.5) -2.465 0.014 谷丙转氨酶/(U·L-1) 17.9(13.0,34.2) 18.2(12.2,28.9) -1.345 0.199 总胆固醇/(mmol·L-1/) 4.13±1.65 3.75±1.26 2.992 0.003 低密度脂蛋白胆固醇/(mmol·L-1) 2.95±1.41 2.24±1.03 6.692 < 0.001 左心室射血分数/% 47.2±12.0 49.6±11.7 -2.237 0.026 B型利钠肽/(pg·mL-1) 420.8(170.9,2731.5) 308.1(102.5,1643.2) -47.115 < 0.001 住院期间心血管治疗用药 β受体阻滞剂 143(75.7) 203(57.7) 17.266 < 0.001 他汀类 104(55.0) 198(56.3) 0.075 0.785 肾素血管紧张素系统阻滞剂 125(66.1) 226(64.2) 0.202 0.653 住院期间服用助睡眠药物情况 服用助睡眠药物人数 45(23.8) 34(9.7) 29.091 < 0.001 服用助睡眠药物频率/(d·周-1) 4.8±1.8 3.9±2.2 4.823 < 0.001 PSQI评分/分 13.1±5.6 6.2±3.1 14.741 < 0.001 表 2 2组患者PSM后的临床基线数据比较

Table 2. General data after PSM

例(%), X±S, M(P25, P75) 项目 心绞痛伴SRI组(187例) 心绞痛不伴SRI组(187例) t/Z/χ2值 P值 年龄/岁 67.4±13.9 67.8±13.3 -0.284 0.776 男性 83(44.4) 84(45.7) 0.011 0.917 吸烟 64(34.2) 63(33.7) 0.012 0.913 BMI/(kg·m-2) 25.4(21.8,27.8) 25.3(21.9,27.7) -1.764 0.078 入院时心率/(次·min-1) 89±21 88±24 0.429 0.668 入院时收缩压/mmHg 136±18 136±17 0.000 1.000 伴随疾病 高血压 59(31.5) 56(29.9) 0.113 0.737 糖尿病 49(26.2) 51(27.3) 0.055 0.815 脑卒中 32(17.1) 34(18.2) 0.074 0.786 白细胞计数/(×109·L-1) 7.93(5.66,11.25) 7.85(5.78,11.10) -1.470 0.142 肌酐/(μmol·L-1) 84.7(66.5,106.3) 85.6(67.8,105.5) -0.119 0.905 谷丙转氨酶/(U·L-1) 17.7(13.9,35.2) 18.1(13.4,33.9) -0.785 0.443 总胆固醇/(mmol·L-1) 4.09±1.75 3.85±1.44 1.448 0.148 低密度脂蛋白胆固醇/(mmol·L-1) 2.85±1.34 2.74±1.15 0.852 0.395 左心室射血分数/% 46.6±12.7 47.3±11.8 -0.552 0.581 B型利钠肽/(pg·mL-1) 422.5(182.3,2732.8) 418.7(178.5,1969.7) -1.012 0.256 住院期间心血管治疗用药 β受体阻滞剂 143(76.5) 144(77.0) 0.015 0.903 他汀类 103(55.1) 106(56.7) 0.098 0.755 肾素血管紧张素系统阻滞剂 125(66.8) 123(65.8) 0.048 0.827 住院期间服用助睡眠药物情况 服用助睡眠药物人数 43(24.1) 28(17.6) 5.031 0.025 服用助睡眠药物频率/(d·周-1) 4.6±1.7 4.1±2.0 2.605 0.010 PSQI评分/分 13.1±4.8 7.1±3.6 13.675 < 0.001 表 3 2组患者PSM前后终点事件发生情况比较

Table 3. The end-point events before and after PSM

例(%) 时间 终点事件 心绞痛伴SRI组 心绞痛不伴SRI组 χ2值 P值 匹配前 全因死亡 10(5.3) 13(3.7) 0.771 0.380 再发心绞痛入院 11(5.8) 14(4.0) 0.948 0.330 再次行冠脉介入治疗或移植手术 10(5.3) 14(4.0) 0.501 0.479 急性心力衰竭 14(7.4) 19(5.4) 0.867 0.352 脑卒中 6(3.2) 8(2.3) 0.397 0.529 合计(复合终点) 51(27.0) 68(19.3) 4.212 0.040 匹配后 全因死亡 10(5.3) 7(3.7) 0.555 0.456 再发心绞痛入院 11(5.9) 8(4.3) 0.499 0.480 再次行冠脉介入治疗或移植手术 9(4.8) 7(3.7) 0.169 0.981 急性心力衰竭 13(7.0) 6(3.2) 2.717 0.099 脑卒中 6(3.2) 3(1.6) 0.502 0.254 合计(复合终点) 49(26.2) 31(16.6) 4.147 0.042 注:匹配前,心绞痛伴SRI组有189例患者,心绞痛不伴SRI组有352例患者;匹配后绞痛伴SRI组和心绞痛不伴SRI组各有187例患者。 表 4 PSM前后SRI与复合终点事件的Cox单因素及多因素回归分析

Table 4. Cox regression analysis of SRI and composite endpoint events before and after PSM

项目 β Wald χ2 P HR 95%CI 匹配前 单因素 0.427 7.229 0.007 2.528 1.599~3.508 多因素 0.351 8.956 0.039 1.852 1.223~2.478 匹配后 单因素 0.226 5.157 0.023 1.897 1.405~2.216 多因素 0.407 6.609 0.042 1.503 1.247~1.811 -

[1] 刘红, 王德玺, 唐向东. 失眠症患者的执行功能[J]. 中华行为医学与脑科学杂志, 2020, 29(7): 666-670. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn371468-20200327-01191

[2] 中国医师协会全科医师分会双心学组, 心血管疾病合并失眠诊疗中国专家共识组. 心血管疾病合并失眠诊疗中国专家共识[J]. 中华内科杂志, 2017, 56(4): 310-315. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2017.04.017

[3] 张斌. 中国失眠障碍诊断和治疗指南[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2016: 1-131.

[4] Nowicki Z, Grabowski K, Cubała WJ, et al. Prevalence of self-reported insomnia in general population of Poland[J]. Psychiatr Pol, 2016, 50(1): 165-173. doi: 10.12740/PP/58771

[5] Zhuang J, Zhan Y, Zhang F, et al. Self-reported insomnia and coronary heart disease in the elderly[J]. Clin Exp Hypertens, 2016, 38(1): 51-55. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2015.1060983

[6] 赵红亮, 李柳, 贾玮玲, 等. 唑吡坦对不稳定型心绞痛伴自述失眠患者的临床疗效[J]. 中国新药与临床杂志, 2019, 38(12): 730-734. doi: 10.14109/j.cnki.xyylc.2019.12.006

[7] 王会军, 李晓燕, 赵秀杰, 等. 唑吡坦对中青年冠心病稳定性心绞痛伴自述失眠患者的影响[J]. 中国医院药学杂志, 2020, 40(6): 688-691+698. doi: 10.13286/j.1001-5213.2020.06.18

[8] 赵红亮, 张慧杰, 高改玲, 等. 唑吡坦对老年不稳定性心绞痛伴自述失眠患者的临床疗效评价[J]. 中国医院药学杂志, 2021, 41(6): 612-615. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZGYZ202106011.htm

[9] 池伟伟, 李巧媛, 王思, 等. 唑吡坦对变异型心绞痛伴自述失眠患者临床疗效、预后及安全性的影响[J]. 中国现代应用药学, 2021, 38(7): 862-866. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XDYD202107016.htm

[10] 中华医学会, 中华医学会杂志社, 中华医学会全科医学分会, 等. 稳定性冠心病基层诊疗指南(2020年)[J]. 中华全科医师杂志, 2021, 20(3): 265-273.

[11] 中华医学会, 中华医学会杂志社, 中华医学会全科医学分会, 等. 非ST段抬高型急性冠状动脉综合征基层诊疗指南(2019年)[J]. 中华全科医师杂志, 2021, 20(1): 6-13. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn114798-20201030-01112

[12] Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research[J]. Psychiatry Res, 1989, 28(2): 193-213.

[13] Laugsand LE, Vatten LJ, Platou C, et al. Insomnia and the risk of acute myocardial infarction: a population study[J]. Circulation, 2011, 124(19): 2073-2081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.025858

[14] Madsen MT, Huang C, Zangger G, et al. Sleep disturbances in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review[J]. J Clin Sleep Med, 2019, 15(3): 489-504. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7684

[15] Wang P, Song L, Wang K, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of poor sleep quality among Chinese older adults living in a rural area: a population-based study[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2020, 32(1): 125-131.

[16] Frøjd LA, Munkhaugen J, Moum T, et al. Insomnia in patients with coronary heart disease: prevalence and correlates[J]. J Clin Sleep Med, 2021, 17(5): 931-938.

[17] von Känel R, Meister-Langraf RE, Pazhenkottil AP, et al. Insomnia symptoms and acute coronary syndrome-induced posttraumatic stress symptoms: a comprehensive analysis of cross-sectional and prospective associations[J]. Ann Behav Med, 2021, 55(10): 1019-1030.

[18] Fang SH, Suzuki K, Lim CL, et al. Associations between sleep quality and inflammatory markers in patients with schizophrenia[J]. Psychiatry Res, 2016, 246: 154-160.

[19] Cosgrave J, Phillips J, Haines R, et al. Revisiting nocturnal heart rate and heart rate variability in insomnia: A polysomnography-based comparison of young self-reported good and poor sleepers[J]. J Sleep Res, 2021, 30(4): e13278.

[20] Nagai M, Hoshide S, Nishikawa M, et al. Sleep duration and insomnia in the elderly: associations with blood pressure variability and carotid artery remodeling[J]. Am J Hypertens, 2013, 26(8): 981-989.

[21] 郝英霞, 贾秀珍. 失眠对老年慢性心衰患者心脏功能的影响[J]. 中国民康医学, 2016, 28(18): 64-66. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZMYX201618028.htm

[22] Oh MS, Bliwise DL, Smith AL, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, sleep symptoms, and their association with cardiovascular disease[J]. Laryngoscope, 2020, 130(6): 1595-1602.

[23] Redeker NS, Knies AK, Hollenbeak C, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in stable heart failure: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial[J]. Contemp Clin Trials, 2017, 55: 16-23.

[24] Hu XM, Wei WT, Huang DY, et al. The Assessment of sleep quality in patients following valve repair and valve replacement for infective endocarditis: a retrospective study at a single center[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2021, 27: e930596.

[25] Hauan M, Strand LB, Laugsand LE. Associations of insomnia symptoms with blood pressure and resting heart rate: The HUNT Study in Norway[J]. Behav Sleep Med, 2018, 16(5): 504-522.

[26] Lo K, Woo B, Wong M, et al. Subjective sleep quality, blood pressure, and hypertension: a meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Hypertens(Greenwich), 2018, 20(3): 592-605.

[27] Fietze I, Laharnar N, Koellner V, et al. The Different faces of insomnia[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2021, 12: 683943.

[28] O'Sullivan ED, Hughes J, Ferenbach DA. Renal aging: causes and consequences[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2017, 28(2): 407-420.

[29] Averyanova IV. Age-related blood biochemical changes(lipid metabolism)in healthy young and mature men living under the North conditions[J]. Klin Lab Diagn, 2021, 66(12): 728-732.

[30] Cao XL, Wang SB, Zhong BL, et al. The prevalence of insomnia in the general population in China: A meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(2): e0170772.

[31] Zeng LN, Zong QQ, Yang Y, et al. Gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia: a meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2020, 11: 577429.

[32] 刘贤臣, 唐茂芹, 胡蕾, 等. 匹兹堡睡眠质量指数的信度和效度研究[J]. 中华精神科杂志, 1996, 20(2): 103-107. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZHMA199602018.htm

[33] Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, et al. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia[J]. J Psychosom Res, 2002, 53(3): 737-740.

[34] Javaheri S, Reid M, Drerup M, et al. Reducing coronary heart disease risk through treatment of insomnia using web-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a methodological approach[J]. Behav Sleep Med, 2020, 18(3): 334-344.

[35] Kim JW, Stewart R, Lee HJ, et al. Sleep problems associated with long-term mortality in acute coronary syndrome: Effects of depression comorbidity and treatment[J]. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 2020, 66: 125-132.

-

下载:

下载: