Construction and Verification of a Prediction Model of Ventricular Fibrillation in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction before primary percutaneous coronary intervention

-

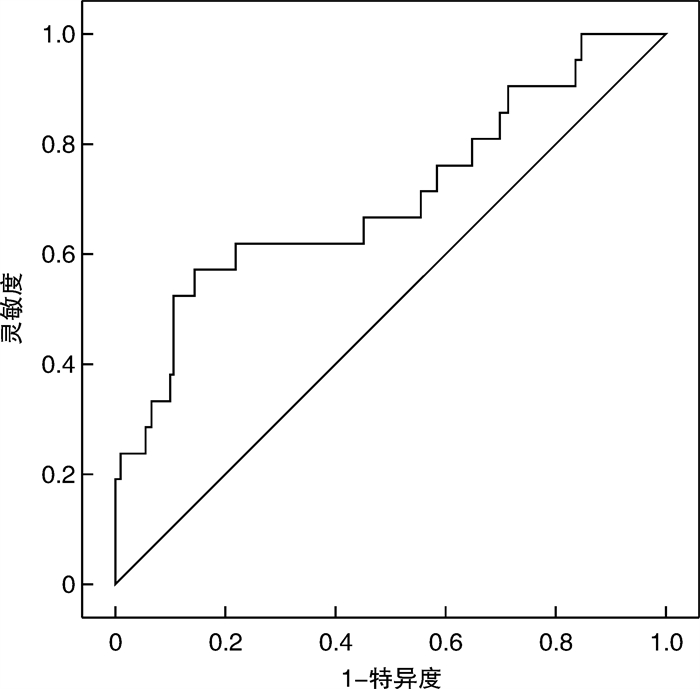

摘要: 目的 构建急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死(ST-segment elevation mayocardial infarction,STEMI)患者急诊介入前心室颤动(室颤)的预测模型并对预测价值进行内部验证。方法 回顾分析2020年1月—2022年5月连续收治的223例STEMI患者,采用多因素logistic回归筛选独立危险因素并构建预测模型。ROC曲线分析预测价值,并利用2022年7~12月另96例STEMI患者数据验证其预测能力。结果 与对照组(202例)比较,室颤组(21例)进急诊室时心率更快、血压更低、Killip分级更高、罪犯血管为前降支比例更高、主动脉气囊反搏使用率更高、存活出院率更低(均P < 0.05);急诊外周血白细胞计数和尿酸水平更高、左室射血分数更低(均P < 0.05)。多因素logistic回归表明急诊室心率、舒张压、尿酸水平和Killip分级为早期室颤的独立影响因素。预测模型(1.05×心率+0.947×舒张压+1.008×尿酸+13.207×Killip分级)的ROC曲线下面积为0.703(95%CI 0.569~0.837,P=0.002),截断值为552.8,灵敏度和特异度分别为57.1%和85.6%。后期内部验证的准确度为0.865,灵敏度为71.4%,特异度为87.6%。结论 利用STEMI患者发病早期临床指标构建的预测模型有助于识别急诊介入前室颤的高危人群。Abstract: Objective The aim was to construct a prediction model of ventricular fibrillation(VF) in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction(STEMI) before primary percutaneous coronary intervention(PPCI) and verify its prediction value.Methods The 223 consecutive patients with STEMI admitted from January 2020 to May 2022 were retrospectively analyzed. Independent risk factors were screened and a prediction model was constructed via multivariate logistic regression. A ROC curve was used to analyze its predictive value and the data of another 96 STEMI patients from July to December 2022 were used for internal validation.Results Compared with the control group(n=202), the VF group(n=21) had faster heart rate, lower blood pressure, higher Killip grade at admission, higher proportion of culprit vessels as left anterior descending arteries, higher proportion of using intra-aortic balloon pulsation, and lower survival and discharge rate(all P < 0.05). As for the VF group, the peripheral blood white blood cell count and uric acid level at admission were higher, the glutamic pyruvic transaminase was higher, and the left ventricular ejection fraction was lower within 24 hours after admission(all P < 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression showed that heart rate, diastolic blood pressure, uric acid level and Killip grade were independent factors of VF. The area under the ROC curve of the prediction model(1.05×heart rate+0.947×diastolic blood pressure+1.008×uric acid+13.207×Killip grade) was 0.703(95%CI 0.569-0.837, P=0.002), with sensitivity and specificity of 57.1% and 85.6%, respectively. The accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the internal verification in the second stage are 0.865, 0.714, 0.876, respectively.Conclusion prediction model constructed by the easy to obtain variables in the early stage of STEMI patients is helpful to identify the high-risk group of VF before PPCI.

-

-

表 1 两组一般临床资料比较

Table 1. General data

例(%), X±S, M(P25, P75) 项目 非室颤组(202例) 室颤组(21例) 统计量 P值 年龄/岁 62(55,71) 61±12 -0.364 0.715 男性 151(74.8) 17(81.0) 0.394 0.530 BMI/(kg/m2) 25.0±3.6 23.8±3.0 1.519 0.130 吸烟 132(65.3) 16(76.2) 1.002 0.317 S2D/h 2.3(1.4,5.0) 2.0(1.5,3.5) -0.339 0.735 高血压 110(54.5) 8(38.1) 2.044 0.153 糖尿病 49(24.3) 6(28.6) 0.191 0.662 脑卒中 19(9.4) 3(14.3) 0.509 0.475 心率/(次/min)* 78(66,85) 91.3±20.6 -3.177 0.001 收缩压/mmHg* 137.9±22.8 120.1±22.0 3.402 0.001 舒张压/mmHg* 81.0±15.6 72.7±12.4 2.374 0.018 Killip心功能分级 64.153 < 0.001 Ⅰ 184(91.1) 8(38.1) Ⅱ 15(7.4) 5(23.9) Ⅲ 2(1.0) 4(19.0) Ⅳ 1(0.5) 4(19.0) Gensini得分 56(37,82) 51(38,83) -0.034 0.913 罪犯血管 11.237 0.011 左前降支 98(48.5) 16(76.2) 左回旋支 23(11.4) 0(0) 右冠脉 80(39.6) 4(19.0) 左主干 1(0.5) 1(4.8) 血管病变支数 0.895 0.639 1 40(19.8) 6(38.6) 2 64(31.7) 6(28.6) 3 98(48.5) 9(42.9) 心脏机械并发症 2(1.0) 0(0) 0.210 1.000 IABP 6(3.0) 5(23.8) 17.616 0.001 存活出院 198(98.0) 18(85.7) 9.474 0.020 S2D:发病至进入急诊时间;IABP:主动脉气囊反搏泵。*均为进入急诊室首次测量值。 表 2 两组血化验及心脏超声指标比较

Table 2. Laboratory and cardiac ultrasound indicators

例(%), X±S, M(P25, P75) 参数 非室颤(202例) 室颤(21例) 统计量 P值 白细胞/(109/L) 9.47(7.90,11.50) 13.65±5.41 -3.293 0.001 血红蛋白/(g/L) 145.6±16.7 150.3±15.6 -1.219 0.224 血小板/(109/L) 214.5(182.8,257.1) 232.9±67.5 -0.721 0.471 血清白蛋白/(g/L) 39.2±3.2 38.4±4.2 1.023 0.307 谷丙转氨酶/(U/L) 41(27.3,63.8) 69(39.5,121.0) -2.743 0.006 谷草转氨酶/(U/L) 188(97.3,291.3) 151(84.5,628) -0.773 0.439 总胆红素/(μmol/L) 13.6(10.2,17) 14.4±6.5 -0.308 0.758 结合胆红素/(μmol/L) 4.4(3.2,5.6) 4.0(3.35,5.48) -0.203 0.839 碱性磷酸酶/(U/L) 71(59,87) 79.1±23.2 -0.634 0.526 γ-谷氨酰转肽酶/(U/L) 25(18,41.5) 30.5(19.3,66) -1.281 0.200 血糖/(mmol/L) 8.09(6.78,10.17) 11.91±6.74 -1.897 0.058 尿素氮/(mmol/L) 5.9±1.4 6.2±1.6 -0.988 0.324 血肌酐/(μmol/L) 69(60,80) 79±20.7 -1.666 0.096 尿酸/(μmol/L) 301.6±86.5 392.4±148.5 -2.754 0.012 血钙/(mmol/L) 2.15±0.10 2.10±0.14 1.637 0.116 血镁/(mmol/L) 0.89(0.83,0.95) 0.90±0.09 -0.041 0.967 血钾/(mmol/L) 3.79±0.45 3.90±0.56 -1.034 0.302 CK-MB峰值/(U/L) 175.5(97.3,288) 137.0(80,438.5) -0.384 0.701 甘油三酯/(mmol/L) 1.37(0.98,1.92) 1.43±0.63 -0.668 0.504 胆固醇/(mmol/L) 4.69(4.1,5.42) 4.84±1.25 -0.166 0.868 HDL-C/(mmol/L) 1.08±0.28 1.10±0.30 -0.291 0.771 LDL-C/(mmol/L) 2.97(2.52,3.49) 3.13±0.88 -0.695 0.487 B型钠尿肽/(pg/mL) 35.7(12.5,111) 51.9(21.1,251) -1.115 0.265 糖化血红蛋白/% 5.9(5.6,6.7) 6(5.6,8.6) -1.020 0.357 纤维蛋白原/(g/L) 3.11(2.68,3.70) 3.20(2.54,3.58) -0.444 0.657 超敏C反应蛋白/(mg/dL) 4.15(2.14,6.59) 5.77(2.24,11.05) -1.258 0.208 左房内径/mm 38(36,41) 37(35,40) -0.841 0.401 左室舒张末内径/mm 46(43,49) 47±4 -0.540 0.589 左室射血分数/% 50(46,54) 45(40,49) -3.308 0.001 HDL-C:高密度脂蛋白胆固醇;LDL-C:低密度脂蛋白胆固醇;CK-MB:肌酸激酶同工酶。血化验指标方面,肝功能、血脂和超敏C反应蛋白检测时间点为发病后第2天清晨空腹状态,CK-MB峰值为发病后10~24 h检测值,其余指标均为进入急诊后即刻。心脏彩超为发病后24 h内(急诊经皮冠脉介入治疗后)。 表 3 STEMI患者急诊介入前室颤的多因素logistic回归分析

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis

变量 OR 95%CI P值 心率 1.050 1.015~1.086 0.004 舒张压 0.947 0.902~0.994 0.186 尿酸 1.008 1.002~1.014 0.011 Killip分级 13.207 3.864~45.143 < 0.001 回归模型:风险得分=1.05×心率+0.947×舒张压+1.008×尿酸+13.207×Killip分级(Killip分级为Ⅰ级时赋1分,killip分级>Ⅰ级均赋2分)。 -

[1] Bhatt DL, Lopes RD, Harrington RA. Diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes: a review[J]. JAMA, 2022, 327(7): 662-75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0358

[2] 魏宇淼. 急性心肌梗死并发心源性休克的当代治疗策略及技术[J]. 临床心血管病杂志, 2021, 37(7): 591-594. doi: 10.13201/j.issn.1001-1439.2021.07.001

[3] 廖付军, 鲍海龙, 韦波, 等. VA-ECMO联合IABP在急性心肌梗死PCI术后并发难治性心源性休克中的应用[J]. 临床心血管病杂志, 2021, 37(11): 992-997. doi: 10.13201/j.issn.1001-1439.2021.11.005

[4] Boehringer T, Bugert P, Borggrefe M, et al. SCN5A mutations and polymorphisms in patients with ventricular fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction[J]. Mol Med Reports, 2014, 10(4): 2039-2044. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2401

[5] Andelova K, Bacova BS, Sykora M, et al. Mechanisms underlying antiarrhythmic properties of cardioprotective agents impacting inflammation and oxidative stress[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(3): 110.

[6] Mitsis A, Kadoglou NPE, Lambadiari V, et al. Prognostic role of inflammatory cytokines and novel adipokines in acute myocardial infarction: An updated and comprehensive review[J]. Cytokine, 2022, 153: 155848. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2022.155848

[7] Glinge C, Sattler S, Jabbari R, et al. Epidemiology and genetics of ventricular fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction[J]. J Ger Cardiol, 2016, 13(9): 789-797. http://www.jgc301.com/ch/reader/create_pdf.aspx?file_no=20160329001&flag=1

[8] Bugert P, Elmas E, Stach K, et al. No evidence for an association between the rs2824292 variant at chromosome 21q21 and ventricular fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction in a German population[J]. Clin Chem Lab Med, 2011, 49(7): 1237-1239. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.190

[9] 徐靖, 程澜. 经皮冠状动脉介入治疗急性ST段抬高心肌梗死患者血管再通过程中发生心室颤动的相关危险因素分析[J]. 中国介入心脏病学杂志, 2016, 24(5), : 247-250. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-8812.2016.05.002

[10] Weizman O, Marijon E, Narayanan K, et al. Incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of ventricular fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction in women admitted alive in the hospital[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2022: e025959.

[11] Mehta RH, Harjai KJ, Grines L, et al. Sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in the cardiac catheterization laboratory among patients receiving primary percutaneous coronary intervention: incidence, predictors, and outcomes[J]. JACC, 2004, 43(10): 1765-1772. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.072

[12] Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction[J]. JACC, 2012, 60(16): 1581-1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001

[13] Tran HV, Ash AS, Gore JM, et al. Twenty-five year trends(1986-2011) in hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction[J]. Am Heart J, 2019, 208: 1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.10.007

[14] Huang J, Peng X, Fang Z, et al. Risk assessment model for predicting ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients who received primary percutaneous coronary intervention[J]. Medicine, 2019, 98(4): e14174. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014174

[15] 张敬, 罗长军. 急性心肌梗死诱发心室颤动机制的研究进展[J]. 心脑血管病防治, 2020, 20(4): 5: 110. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XXFZ202004017.htm

[16] 王旭, 祖晓麟, 王成钢, 等. 急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死并发心室颤动患者冠状动脉造影特点[J]. 中国医药, 2013, 8(8): 110.

[17] 潘兴飞, 郑常龙, 邹小芳. 急性心肌梗死患者院内并发心室颤动的危险因素分析[J]. 广东医学, 2016, 37(9): 3. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-GAYX201609015.htm

[18] Mahtta D, Sudhakar D, Koneru S, et al. Targeting inflammation after myocardial infarction[J]. Cur Cardiol Reports, 2020, 22(10): 110. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01358-2

[19] Li J, Wang L, Wang Q, et al. Diagnostic value of carotid artery ultrasound and hypersensitive C-reactive protein in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with acute myocardial infarction in Chinese population[J]. Medicine, 2018, 97(41): e12334. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012334

[20] Wang L, Liao B, Yu J, et al. Changes of cardiac troponin I and hypersensitive C-reactive protein prior to and after treatment for evaluating the early therapeutic efficacy of acute myocardial infarction treatment[J]. Exper Therap Med, 2020, 19(2): 1121-1128.

[21] Carrero JJ, Andersson Franko M, Obergfell A, et al. hsCRP Level and the Risk of Death or Recurrent Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Myocardial Infarction: a Healthcare-Based Study[J]. J Am Heart Associ, 2019, 8(11): e012638. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012638

[22] 张忠印, 钱开成, 于银坤. 急性心肌梗死患者血清超敏C反应蛋白测定及临床意义[J]. 现代医药卫生, 2007, 23(6): 2-5. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XYWS200706012.htm

[23] 房亚哲, 郭楠, 聂庆东, 等. 北京地区中老年人同型半胱氨酸参考区间的建立及与尿酸相关性分析[J]. 临床心血管病杂志, 2022, 38(4): 314-317. https://lcxxg.whuhzzs.com/article/doi/10.13201/j.issn.1001-1439.2022.04.012

[24] Kroll K, Bukowski TR, Schwartz LM, et al. Capillary endothelial transport of uric acid in guinea pig heart[J]. Am J Physiology, 1992, 262(2 Pt 2): H420-431. http://www.onacademic.com/detail/journal_1000041635160199_bc6e.html

[25] Dewi IP, Putra KNS, Dewi KP, et al. Serum uric acid and the risk of ventricular arrhythmias: a systematic review[J]. Kardiologiia, 2022, 62(6): 70-73.

[26] Chen L, Li XL, Qiao W, et al. Serum uric acid in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction[J]. World J Emergency Med, 2012, 3(1): 35-39. http://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23960675/

[27] Car S, Trkulja V. Higher serum uric acid on admission is associated with higher short-term mortality and poorer long-term survival after myocardial infarction: retrospective prognostic study[J]. Croatian Med J, 2009, 50(6): 559-566. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20017224

[28] Omidvar B, Ayatollahi F, Alasti M. The prognostic role of serum uric acid level in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction[J]. J Saudi Heart Assoc, 2012, 24(2): 73-78.

[29] Czifra Á, Páll A, Sebestyén V, et al. End stage renal disease and ventricular arrhythmia. Hemodialysis and hemodiafiltration differently affect ventricular repolarization[J]. Orvosi Hetilap, 2015, 156(12): 463-471.

[30] Lisowska A, Tycińska A, Knapp M, et al. The incidence and prognostic significance of cardiac arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities in patients with acute coronary syndromes and renal dysfunction[J]. Kardiologia Polska, 2011, 69(12): 1242-1247. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883944110002297

[31] Luo J, Shaikh JA, Huang L, et al. Human plasma metabolomics identify 9-cis-retinoic acid and dehydrophytosphingosine levels as novel biomarkers for early ventricular fibrillation after ST-elevated myocardial infarction[J]. Bioengineered, 2022, 13(2): 3334-3350. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21655979.2022.2027067

-

下载:

下载: