Ratio of monocyte to high-density lipoprotein and clinical outcomes in patients with acute decompensated heart failure

-

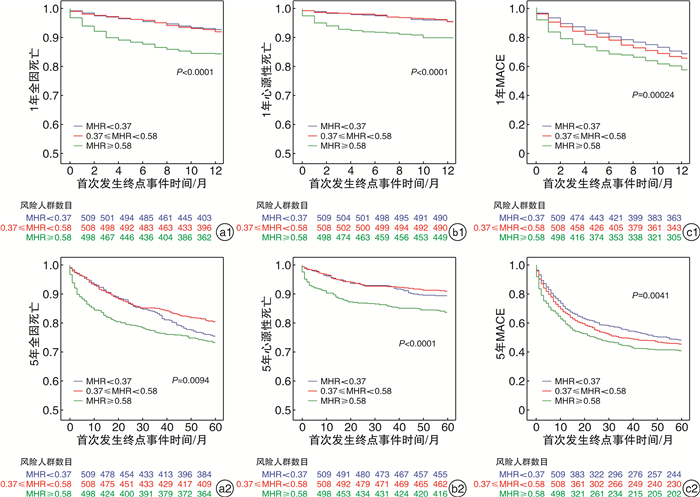

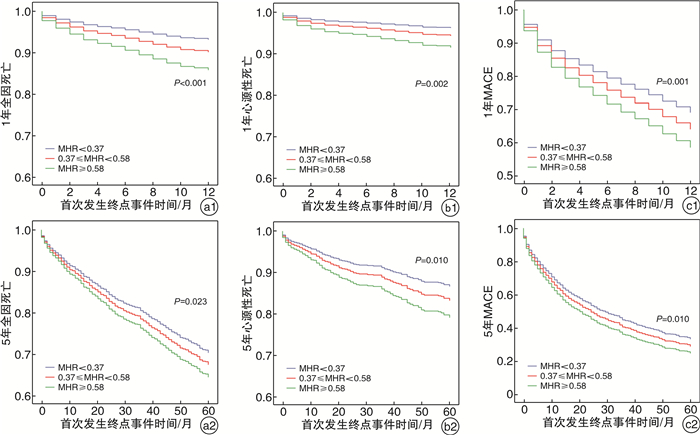

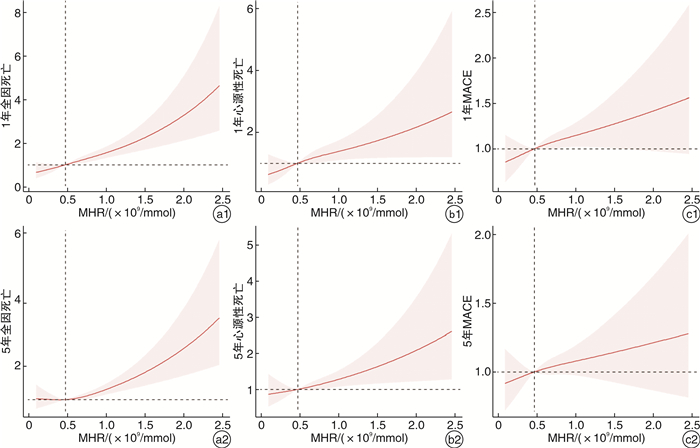

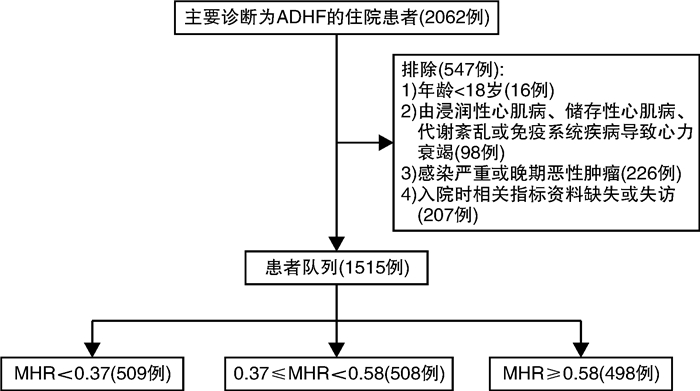

摘要: 目的 探讨单核细胞计数与高密度脂蛋白浓度比值(MHR)与急性失代偿性心力衰竭(ADHF)患者的临床预后的关系。方法 2012年11月—2019年12月于南京鼓楼医院心血管内科因主要诊断为ADHF住院的1 515例患者被纳入研究。根据MHR值,将患者按三分位数分为3组:第1三分位组(T1组),MHR<0.38;第2三分位组(T2组),0.38≤MHR<0.58;第3三分位组(T3组),MHR≥0.58。终点事件包括全因死亡、心源性死亡和主要不良心血管事件(MACE)。通过多因素Cox比例风险模型分析MHR与临床结局的相关性。结果 在5年随访期间,共28.0%(358例)患者发生全因死亡,12.0%(182例)发生心源性死亡,55.4%(839例)发生MACE。校正混杂因素后,与T1组相比,T3组5年内全因死亡、心源性死亡及MACE风险增加(校正全因死亡HR:1.35,95%CI 1.04~1.77,P=0.023;校正心源性死亡HR:1.57,95%CI 1.08~2.28,P=0.010;校正MACE HR:1.26,95%CI 1.06~1.51,P=0.010)。结论 MHR升高后ADHF患者全因死亡、心源性死亡及MACE风险增加。

-

关键词:

- 单核细胞计数与高密度脂蛋白浓度比值 /

- 急性失代偿性心力衰竭 /

- 预后

Abstract: Objective To explore the relationship between monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio(MHR) and the clinical prognosis of patients with acute decompensated heart failure(ADHF).Methods A total of 1 515 hospitalized patients with ADHF from November, 2012 to December, 2019 were included in this retrospective study. Enrolled patients were divided into three groups by tertile of MHR: Tertile 1(T1), MHR < 0.38; Tertile 2(T2), 0.38≤MHR < 0.58; Tertile 3(T3), MHR≥0.58. Endpoints included all-cause death, cardiovascular death, and major adverse cardiac events(MACE). Multivariate adjusted Cox hazard Proportional models were fitted to investigate the association of MHR with clinical outcomes.Results During the 5-year follow-up period, all-cause death, cardiovascular death and MACE occurred in 358(28.0%), 182(12.0%) and 839(55.4%) cases, respectively. In multivariate Cox proportional hazard models, the risk of incident primary endpoints was associated with the highest MHR tertile. After adjustment for confounding factors, hazard ratios(HRs) for the highest tertile(MHR≥0.58) versus the lowest tertile(MHR < 0.38) were 1.35(95%CI1.04-1.77; P=0.023) for all-cause death, 1.57(95%CI1.08-2.28; P=0.010) for cardiovascular death and 1.26(95%CI1.06-1.51; P=0.010) for MACE.Conclusion Elevated MHR was directly associated with an increase in all-cause death, cardiovascular death and MACE in patients with ADHF. -

-

表 1 按MHR三分位数分组的基线特征

Table 1. General data

例(%), M(P25, P75) 项目 总计(1 515例) T1组(509例) T2组(508例) T3组(498例) P值 女性 649(42.8) 273(53.6) 201(39.6) 175(35.2) <0.0011)2) 年龄/岁 74.00(64.50,81.00) 75.00(66.00,82.00) 75.00(65.00,81.00) 73.00(62.00,80.00) 0.0032)3) 体重指数/(kg/m2) 23.63(21.85,25.39) 23.39(21.74,24.97) 23.65(21.78,25.51) 23.84(22.15,25.70) 0.0182) NYHA Ⅲ和Ⅳ级 1175(77.6) 373(73.3) 387(76.2) 414(83.3) <0.0012)3) 吸烟 341(22.5) 86(16.9) 125(24.6) 130(26.2) 0.0011)2) 饮酒 159(10.5) 37(7.3) 65(12.8) 57(11.5) 0.0111)2) 糖尿病 473(31.2) 126(24.8) 169(33.3) 178(35.8) <0.0011)2) 高血压 1006(66.4) 335(65.8) 359(70.7) 312(62.8) 0.0283) 冠状动脉粥样硬化 566(37.4) 164(32.2) 215(42.3) 187(37.6) 0.0041) 冠状动脉移植史 395(26.1) 123(24.2) 154(30.3) 118(23.7) 0.0291)3) 既往心肌梗死 202(13.3) 49(9.6) 75(14.8) 78(15.7) 0.0091)2) 既往卒中 346(22.8) 108(21.2) 111(21.9) 127(25.6) 0.21 心脏瓣膜病 228(15.0) 77(15.1) 68(13.4) 83(16.7) 0.34 心房颤动 755(49.8) 256(50.3) 249(49.0) 250(50.3) 0.895 贫血 359(23.7) 138(27.1) 102(20.1) 118(23.7) 0.0311) ACEI/ARB 628(41.5) 231(45.4) 214(42.1) 183(36.8) 0.0212) β受体阻滞剂 974(64.3) 301(59.1) 346(68.1) 327(65.8) 0.0081)2) 钙通道阻滞剂 313(20.7) 109(21.4) 116(22.8) 88(17.7) 0.117 利尿剂 1159(76.5) 380(74.7) 374(73.6) 404(81.3) 0.0082)3) 抗血小板药物 723(47.7) 240(47.2) 246(48.4) 237(47.7) 0.92 抗凝药物 422(27.9) 140(27.5) 146(28.7) 136(27.4) 0.866 他汀药物 802(52.9) 249(48.9) 293(57.7) 260(52.3) 0.0192) LVEF/% 46.00(36.00,54.00) 48.00(39.00,55.00) 45.00(37.00,55.00) 44.00(34.00,53.00) <0.0012)3) 左室舒张期内径/cm 5.60(5.05,6.30) 5.59(5.04,6.14) 5.64(5.10,6.35) 5.65(5.04,6.45) 0.069 肺动脉压力/mmHg 42.00(35.00,50.00) 41.00(35.00,50.00) 42.00(35.00,50.00) 42.00(35.00,50.00) 0.706 MHR/(×109/mmoL) 0.47(0.32,0.66) 0.28(0.22,0.32) 0.47(0.41,0.52) 0.79(0.66,1.02) <0.0011)2)3) 总胆固醇/(mmol/L) 3.64(3.02,4.40) 3.90(3.25,4.59) 3.62(3.03,4.37) 3.38(2.84,4.11) <0.0011)2)3) 甘油三酯/(mmol/L) 1.03(0.75,1.45) 0.94(0.67,1.28) 1.08(0.78,1.57) 1.09(0.81,1.52) <0.0011)2) LDL-C/(mmol/L) 1.93(1.47,2.49) 1.97(1.51,2.54) 1.93(1.48,2.51) 1.90(1.40,2.46) 0.186 HDL-C/(mmol/L) 0.96(0.78,1.20) 1.22(1.04,1.43) 0.95(0.85,1.10) 0.75(0.61,0.88) <0.0011)2)3) B型利钠肽/(μmol/L) 527.00(233.00,932.50) 450.00(201.00,819.00) 524.00(266.75,886.00) 576.00(275.00,1140.00) <0.0011)2)3) 白细胞计数/(×109/L) 6.20(5.00,7.70) 5.10(4.30,6.20) 6.30(5.30,7.50) 7.50(6.00,9.10) <0.0011)2)3) 中性粒细胞比例/% 66.80(59.80,74.00) 65.70(58.60,73.70) 66.10(59.50,72.20) 68.90(61.40,76.60) <0.0012)3) 单核细胞比例/% 7.30(5.90,8.90) 6.30(5.10,7.60) 7.30(6.00,8.50) 8.50(7.10,10.20) <0.0011)2)3) 血红蛋白/(g/L) 128.00(112.00,140.00) 125.00(109.00,137.00) 129.00(115.00,143.00) 129.00(112.00,142.00) 0.0011)2) eGFR/(mL/min) 70.00(48.00,87.00) 74.00(52.00,88.00) 70.00(48.00,86.97) 65.00(44.55,87.00) 0.099 血肌酐/(μmol/L) 83.00(67.00,110.00) 79.00(63.00,103.00) 86.00(68.88,108.05) 87.00(70.00,119.00) <0.0012)3) 血尿酸/(μmol/L) 427.50(338.00,539.00) 387.00(316.00,490.00) 436.00(350.00,535.25) 461.50(357.00,593.50) <0.0011)2)3) 血钾/(mmol/L) 3.96(3.68,4.28) 3.95(3.71,4.24) 3.98(3.67,4.30) 3.93(3.65,4.28) 0.647 血钠/(mmol/L) 141.00(138.20,142.90) 141.60(139.00,143.60) 141.00(138.40,142.90) 140.20(137.20,142.30) <0.0012)3) 空腹血糖/(mmol/L) 5.10(4.55,6.12) 4.94(4.47,5.71) 5.13(4.59,6.11) 5.31(4.60,6.62) <0.0011)2) 糖化血红蛋白/% 6.14(5.80,6.80) 6.02(5.70,6.50) 6.16(5.80,6.70) 6.37(5.90,7.10) <0.0011)2)3) C反应蛋白/(mg/L) 4.30(2.40,10.20) 3.40(2.00,5.50) 3.70(2.30,7.23) 8.20(3.50,28.90) <0.0011)2)3) 白蛋白/(g/L) 38.10(35.50,40.70) 38.80(36.20,41.10) 38.30(36.00,41.00) 36.90(34.10,39.80) <0.0012)3) 丙氨酸转氨酶/(U/L) 19.30(13.40,30.50) 17.90(12.60,25.90) 19.10(13.05,29.15) 22.90(14.50,40.35) <0.0012)3) 天冬氨酸转氨酶/(U/L) 23.20(18.00,31.67) 22.60(18.15,29.55) 22.30(17.70,30.00) 24.70(18.35,36.00) <0.0012)3) T1组与T2组比较,1)P<0.05;T1组与T3组比较,2)P<0.05;T2组与T3组比较,3)P<0.05。 表 2 MHR与全因死亡、心源性死亡和MACE的关系(作为分类变量)

Table 2. Relationship between MHR and all-cause death, cardiac death and MACE

未校正 模型1 模型2 模型3 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 1年 全因死亡 T1 参考 参考 参考 参考 T2 1.14(0.71~1.74) 0.635 1.1(0.72~1.76) 0.598 1.11(0.71~1.75) 0.64 1.16(0.73~1.85) 0.506 T3 2.31(1.56 ~3.41) <0.001 2.54(1.72~3.78) <0.001 2.38(1.60~3.57) <0.001 2.33(1.53~3.54) <0.001 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值<0.001 心源性死亡 T1 参考 参考 参考 参考 T2 1.00(0.55~1.84) 0.986 1.02(0.55~1.87) 0.959 0.92(0.49~-1.70) 0.785 0.94(0.50~1.75) 0.839 T3 2.49(1.49~4.15) <0.001 2.68(1.59~4.49) <0.001 2.37(1.40~4.02) 0.001 2.17(1.25~3.78) 0.006 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值=0.002 MACE T1 参考 参考 参考 参考 T2 1.15(0.97~1.36) 0.235 1.16(0.98~1.37) 0.223 1.09(0.92~1.30) 0.586 1.09(0.87~1.37) 0.457 T3 1.38(1.17~1.63) <0.001 1.44(1.22~1.70) <0.001 1.30(1.10~1.54) 0.001 1.44(1.15~1.80) 0.001 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值=0.002 趋势P值=0.001 5年 全因死亡 T1 参考 参考 参考 参考 T2 0.81(0.62~1.06) 0.12 0.81(0.62~1.06) 0.128 0.79(0.60~1.03) 0.082 0.83(0.63~1.09) 0.178 T3 1.21(0.95~1.55) 0.122 1.36(1.06~1.74) 0.014 1.30(1.01~1.68) 0.04 1.35(1.04~1.77) 0.025 趋势P值=0.128 趋势P值=0.017 趋势P值=0.041 趋势P值=0.023 心源性死亡 T1 参考 参考 参考 参考 T2 0.87(0.59~1.29) 0.489 0.87(0.58~1.29) 0.483 0.80(0.53~1.20) 0.277 0.79(0.53~1.19) 0.266 T3 1.69(1.20~2.39) 0.003 1.84(1.30~2.61) 0.001 1.69(1.18~2.41) 0.004 1.57(1.08~2.28) 0.019 趋势P值=0.002 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值=0.002 趋势P值=0.010 MACE T1 参考 参考 参考 参考 T2 1.15(0.97~1.36) 0.108 1.16(0.98~1.37) 0.088 1.09(0.92~1.30) 0.305 1.08(0.91~1.29) 0.378 T3 1.38(1.17~1.63) <0.001 1.44(1.22~1.70) <0.001 1.30(1.10~1.54) 0.002 1.26(1.06~1.51) 0.010 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值<0.001 趋势P值=0.002 趋势P值=0.010 表 3 MHR与全因死亡、心源性死亡和MACE的关系(作为连续变量)

Table 3. Relationship between MHR and all-cause death, cardiac death and MACE

未校正(每增加1个单位) 模型1(每增加1个单位) 模型2(每增加1个单位) 模型3(每增加1个单位) HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 1年 全因死亡 2.39(1.88~3.04) <0.001 2.53(2.01~3.19) <0.001 2.37(1.84~3.05) <0.001 2.21(1.68~2.90) <0.001 心源性死亡 2.25(1.62~3.14) <0.001 2.36(1.71~3.26) <0.001 1.96(1.40~2.74) <0.001 1.71(1.18~2.47) 0.004 MACE 1.37(1.12~1.66) 0.002 1.44(1.18~1.75) <0.001 1.32(1.08~1.61) 0.008 1.29(1.04~1.60) 0.021 5年 全因死亡 1.59(1.26~2.01) <0.001 1.84(1.47~2.32) <0.001 1.70(1.35~2.14) <0.001 1.71(1.34~2.18) <0.001 心源性死亡 1.80(1.33~2.43) <0.001 1.99(1.49~2.68) <0.001 1.77(1.31~2.39) <0.001 1.60(1.16~2.21) 0.005 MACE 1.26(1.06~1.48) 0.008 1.32(1.12~1.57) 0.001 1.22(1.02~1.45) 0.028 1.22(1.00~1.48) 0.045 模型1:性别、年龄;模型2:模型1+体重指数、NYHA分级、吸烟、饮酒、糖尿病、高血压、既往心梗、冠状动脉旁路移植史、贫血、β受体组阻滞剂、ACEI/ARB、利尿剂、抗凝药物;模型3:模型2+LVEF、总胆固醇、甘油三酯、中性粒细胞比例、血红蛋白、血肌酐、CRP、BNP。 -

[1] Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, Vaduganathan M, et al. The vulnerable phase after hospitalization for heart failure[J]. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2015, 12(4): 220-229. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.14

[2] Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America[J]. Circulation, 2017, 136(6): 110.

[3] McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure[J]. Euro Heart J, 2021, 42(36): 3599-3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

[4] 高蓉蓉, 徐芳, 祝绪. 全血细胞衍生的炎症标志物对急性心力衰竭患者的长期预后价值[J]. 临床心血管病杂志, 2022, 38(12): 980-987. doi: 10.13201/j.issn.1001-1439.2022.12.010

[5] Mann DL. Inflammatory mediators and the failing heart: past, present, and the foreseeable future[J]. Circ Res, 2002, 91(11): 988-998. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000043825.01705.1B

[6] Gullestad L, Ueland T, Vinge LE, et al. Inflammatory cytokines in heart failure: mediators and markers[J]. Cardiology, 2012, 122(1): 23-35. doi: 10.1159/000338166

[7] Belge KU, Dayyani F, Horelt A, et al. The proinflammatory CD14+CD16+DR++ monocytes are a major source of TNF[J]. J Immunol, 2002, 168(7): 3536-3542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3536

[8] Fritzenwanger M, Meusel K, Foerster M, et al. Cardiotrophin-1 induces interleukin-6 synthesis in human monocytes[J]. Cytokine, 2007, 38(3): 137-144. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.05.015

[9] Maekawa Y, Anzai T, Yoshikawa T, et al. Prognostic significance of peripheral monocytosis after reperfused acute myocardial infarction: a possible role for left ventricular remodeling[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2002, 39(2): 241-246. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01721-1

[10] Velagaleti RS, Massaro J, Vasan RS, et al. Relations of lipid concentrations to heart failure incidence: the Framingham Heart Study[J]. Circulation, 2009, 120(23): 2345-2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.830984

[11] Yvan-Charvet L, Pagler T, Gautier EL, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporters and HDL suppress hematopoietic stem cell proliferation[J]. Science, 2010, 328(5986): 1689-1693. doi: 10.1126/science.1189731

[12] Zhang DP, Baituola G, Wu TT, et al. An elevated monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol ratio is associated with mortality in patients with coronary artery disease who have undergone PCI[J]. Bioscience Reports, 2020, 40(8): BSR20201108. doi: 10.1042/BSR20201108

[13] Cetin MS, Ozcan Cetin EH, Kalender E, et al. Monocyte to HDL cholesterol ratio predicts coronary artery disease severity and future major cardiovascular adverse events in acute coronary syndrome[J]. Heart Lung Circ, 2016, 25(11): 1077-1086. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.02.023

[14] Canpolat U, Aytemir K, Yorgun H, et al. The role of preprocedural monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio in prediction of atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryoballoon-based catheter ablation[J]. Europace, 2015, 17(12): 1807-1815. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu291

[15] Xu Q, Wu Q, Chen L, et al. Monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio predicts clinical outcomes after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack[J]. CNS Neurosci Ther, 2023, 29(7): 1953-1964. doi: 10.1111/cns.14152

[16] Lundgreen CS, Larson DR, Atkinson EJ, et al. Adjusted survival curves improve understanding of multivariable Cox model results[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2021, 36(10): 3367-3371. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.06.002

[17] Jiang M, Yang J, Zou H, et al. Monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol ratio(MHR)and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a nationwide cohort study in the United States[J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2022, 21(1): 30. doi: 10.1186/s12944-022-01638-6

[18] Zhang Y, Li S, Guo YL, et al. Is monocyte to HDL ratio superior to monocyte count in predicting the cardiovascular outcomes[J]. Ann Med, 2016, 48(5): 305-312. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2016.1168935

[19] Liu HT, Jiang ZH, Yang ZB, et al. Monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio predict long-term clinical outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of 9 studies[J]. Medicine(Baltimore), 2022, 101(33): e30109.

[20] Baumgarten G, Knuefermann P, Kalra D, et al. Load-dependent and-independent regulation of proinflammatory cytokine and cytokine receptor gene expression in the adult mammalian heart[J]. Circulation, 2002, 105(18): 2192-2197. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000015608.37608.18

[21] Janssen SP, Gayan-Ramirez G, Van den Bergh A, et al. Interleukin-6 causes myocardial failure and skeletal muscle atrophy in rats[J]. Circulation, 2005, 111(8): 996-1005. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156469.96135.0D

[22] Franco F, Thomas GD, Giroir B, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and invasive evaluation of development of heart failure in transgenic mice with myocardial expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha[J]. Circulation, 1999, 99(3): 448-454. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.3.448

[23] Torre-Amione G, Kapadia S, Benedict C, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction: a report from the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction(SOLVD)[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 1996, 27(5): 1201-1206. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00589-7

[24] Ballou SP, Lozanski G. Induction of inflammatory cytokine release from cultured human monocytes by C-reactive protein[J]. Cytokine, 1992, 4(5): 361-368. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(92)90079-7

[25] Hirano T, Yasukawa K, Harada H, et al. Complementary DNA for a novel human interleukin(BSF-2) that induces B lymphocytes to produce immunoglobulin[J]. Nature, 1986, 324(6092): 73-76. doi: 10.1038/324073a0

[26] Tso C, Martinic G, Fan WH, et al. High-density lipoproteins enhance progenitor-mediated endothelium repair in mice[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2006, 26(5): 1144-1149. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000216600.37436.cf

[27] Spieker LE, Sudano I, Hürlimann D, et al. High-density lipoprotein restores endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic men[J]. Circulation, 2002, 105(12): 1399-1402. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000013424.28206.8F

[28] Mackness MI, Arrol S, Abbott C, et al. Protection of low-density lipoprotein against oxidative modification by high-density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase[J]. Atherosclerosis, 1993, 104(1-2): 129-35. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(93)90183-U

-

下载:

下载: