Correlation between cerebral microbleeds and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease undergoing antithrombotic therapy

-

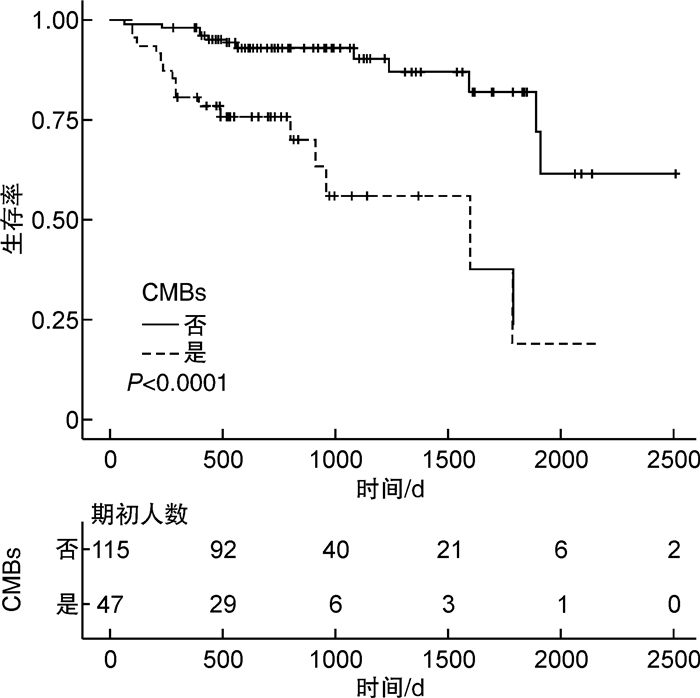

摘要: 目的 观察冠心病抗栓治疗患者脑微出血(CMBs)分布及数目与主要不良心血管事件发生风险的关系。方法 本研究入选2015年5月—2020年1月我院老年内科住院的已诊断冠心病、服用至少一种抗栓药物且完成头颅MRI的患者。根据是否存在CMBs分为CMBs组和非CMBs组,比较2组临床资料、主要不良心血管事件发生情况,发生主要不良心血管事件的危险因素及CMBs分布、数目对预后的影响。结果 共162例患者纳入研究,47例(29.0%)存在CMBs。与非CMBs组比较,CMBs组白蛋白更低,超敏C反应蛋白更高,阿司匹林与替格瑞洛联用及单用抗凝药比例更高(P< 0.05)。CMBs组出血性和缺血性卒中发生率明显高于非CMBs组(P< 0.001)。多因素Cox回归分析显示CMBs是冠心病抗栓治疗患者发生主要不良心血管事件的独立危险因素(HR=4.01,95%CI:1.67~9.62,P=0.002)。随着CMBs数目增多,出血性和缺血性卒中风险明显升高。结论 CMBs是冠心病抗栓治疗患者发生主要不良心血管事件的独立危险因素;随着CMBs数目增多,出血性和缺血性卒中风险明显升高。Abstract: Objective To investigate the correlation between cerebral microbleeds(CMBs) and major adverse cardiovascular events(MACE) in patients with coronary heart disease(CHD) undergoing antithrombotic therapy.Methods This is a single-center retrospective study. CHD patients taking at least one thrombotic agent who underwent brain MRI from May 2015 to January 2020 were included. The patients were divided into two groups: the CMBs group and the non-CMBs group. The clinical data and incidence of MACE were compared between the two groups. The independent predictors of MACE were determined by the Cox regression model and the distribution and quantity of CMBs were also analyzed.Results A total of 162 patients were enrolled in this study, CMBs were identified in 47(29.0%) patients. The patients with CMBs had lower albumin levels, higher c-reactive protein levels, a higher percentage of taking aspirin and ticagrelor or only anticoagulant(P< 0.05). The rates of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke were significantly higher in patients with CMBs than those without(P< 0.001). A multivariate cox regression analysis revealed that the presence of CMBs was independently correlated with the occurrence of MACE after adjusting for major confounding factors(hazard ratio 4.01, 95%CI: 1.67~9.62,P=0.002). Increasing CMBs burden category was associated with the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.Conclusion CMBs was independently correlated with the occurrence of MACE in CHD patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Thw risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke increased with the quantity of CMBs.

-

-

表 1 所有患者临床资料

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the study participants

例(%), X±S 项目 所有患者(162例) CMBs组(47例) 非CMBs组(115例) P值 年龄/岁 72.92±10.27 75.17±10.30 72.00±10.16 0.072 男性 115(70.99) 34(72.34) 81(70.43) 0.808 BMI/(kg·m-2) 25.28±3.50 24.84±3.74 25.46±3.40 0.294 心肌梗死史 48(29.63) 12(25.53) 36(31.30) 0.465 PCI史 92(56.79) 29(61.70) 63(54.78) 0.420 CABG史 17(10.49) 7(14.89) 10(8.70) 0.243 冠脉多支病变 101(62.35) 31(65.96) 70(60.87) 0.544 房颤/房扑 40(24.69) 16(34.04) 24(20.87) 0.078 缺血性卒中史 49(30.25) 16(34.04) 33(28.70) 0.501 高血压 131(80.86) 39(82.98) 92(80.00) 0.662 血脂异常 161(99.38) 46(97.87) 115(100.00) 0.117 LDL-C/(mmol·L-1) 2.06±0.66 1.92±0.59 2.12±0.68 0.054 HDL-C/(mmol·L-1) 1.02±0.26 1.02±0.27 1.03±0.26 0.575 TG/(mmol·L-1) 1.56±0.99 1.37±0.71 1.64±1.08 0.106 糖尿病 74(45.68) 18(38.30) 56(48.70) 0.228 HbA1c/% 6.69±1.45 6.43±1.24 6.80±1.52 0.151 血红蛋白/(g·L-1) 130.81±17.52 127.62±17.55 132.11±17.42 0.124 血小板/(×109·L-1) 179.64±49.67 170.68±48.17 183.30±50.02 0.143 PT/s 11.56±1.59 11.65±1.05 11.52±1.77 0.129 APTT/s 31.20±3.83 31.89±3.91 30.92±3.78 0.103 ALT/(IU·L-1) 22.43±13.23 20.04±8.34 23.41±14.70 0.142 血肌酐/(μmol·L-1) 102.40±82.03 103.57±51.00 101.93±91.93 0.559 eGFR/[(mL·min-1·(1.73 m2)-1] 66.67±19.33 64.06±19.75 67.74±19.14 0.273 eGFR分组 0.587 ≥90 mL·min-1·(1.73 m2)-1 23(14.20) 4(8.51) 19(16.52) 60~89 mL·min-1·(1.73 m2)-1 77(47.53) 24(51.06) 53(46.09) 45~59 mL·min-1·(1.73 m2)-1 46(28.40) 12(25.53) 34(29.57) 30~44 mL·min-1·(1.73 m2)-1 10(6.17) 4(8.51) 6(5.22) 15~29 mL·min-1·(1.73 m2)-1 4(2.47) 2(4.26) 2(1.74) < 15 mL·min-1·(1.73 m2)-1 2(1.23) 1(2.13) 1(0.87) 白蛋白/(g·L-1) 40.09±3.99 38.71±3.45 40.65±4.07 0.005 hsCRP/(mg·L-1) 2.72±4.76 4.06±7.60 2.17±2.74 0.022 HCY/(μmol·L-1) 14.97±5.51 13.73±5.32 15.47±5.53 0.062 吸烟 0.968 从不 82(50.62) 24(51.06) 58(50.43) 是 47(29.01) 14(29.79) 33(28.70) 已戒 33(20.37) 9(19.15) 24(20.87) 饮酒 0.711 从不 104(64.20) 31(65.96) 73(63.48) 是 44(27.16) 11(23.40) 33(28.70) 已戒 14(8.64) 5(10.64) 9(7.83) 抗栓药物 仅阿司匹林 57(35.19) 16(34.04) 41(35.65) 0.846 仅氯吡格雷 7(4.32) 2(4.26) 5(4.35) 0.979 DAPT1 59(36.42) 12(25.53) 47(40.87) 0.066 DAPT2 2(1.23) 2(4.26) 0(0) 0.026 仅OAC 18(11.11) 9(19.15) 9(7.83) 0.037 SAPT+OAC 15(9.26) 5(10.64) 10(8.70) 0.699 DAPT+OAC 4(2.47) 1(2.13) 3(2.61) 0.858 注:DAPT为双联抗血小板治疗,DAPT1指阿司匹林与氯吡格雷联用,DAPT2指阿司匹林与替格瑞洛联用,OAC为口服抗凝药,SAPT为单药抗血小板治疗。 表 2 CMBs与主要不良心血管事件的关系

Table 2. the relationship between CMBs and major adverse cardiovascular events

例(%) 项目 CMBs组(47例) 非CMBs组(115例) P值 心血管死亡 2(4.26) 1(0.87) 0.147 非致死性心肌梗死 1(2.13) 0(0) 0.117 行冠状动脉血运重建 5(10.64) 9(7.83) 0.563 出血性卒中 5(10.64) 1(0.87) 0.003 缺血性卒中 5(10.64) 1(0.87) 0.003 出血性+缺血性卒中 10(21.28) 2(1.74) < 0.001 主要不良心血管事件 16(34.04) 12(10.43) < 0.001 表 3 主要不良心血管事件的单因素及多因素Cox风险回归分析

Table 3. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses for major adverse cardiovascular events

项目 单因素回归分析 多因素回归分析 HR 95%CI P HR 95%CI P CMBs 4.93 2.30~10.55 < 0.0001 4.01 1.67~9.62 0.002 年龄 1 0.96~1.03 0.819 性别 0.48 0.18~1.26 0.137 BMI 0.98 0.87~1.10 0.708 心肌梗死史 2.63 1.25~5.53 0.011 3.26 1.38~7.72 0.007 PCI史 1.38 0.63~3.00 0.418 CABG史 0.34 0.05~2.50 0.289 冠脉多支病变 1.74 0.74~4.11 0.207 房颤/房扑 1.25 0.52~3.01 0.612 缺血性卒中史 2.05 0.97~4.36 0.062 1.56 0.67~3.67 0.303 高血压 0.53 0.24~1.17 0.118 血脂异常 0.10 0.01~0.76 0.026 0.57 0.05~6.37 0.651 糖尿病 0.64 0.29~1.38 0.256 血红蛋白 0.99 0.97~1.02 0.522 血小板 0.99 0.98~1.00 0.037 0.99 0.98~1.00 0.140 PT 1.14 0.97~1.33 0.100 APTT 1.04 0.95~1.14 0.379 ALT 0.97 0.93~1.01 0.144 eGFR < 45 mL·min-1·(1.73m2)-1 3.51 1.29~9.56 0.014 1.49 0.47~4.71 0.498 白蛋白 0.83 0.75~0.93 0.0007 0.87 0.77~0.99 0.028 hsCRP 1.02 0.96~1.08 0.556 HCY 1.03 0.96~1.11 0.374 SAPT 0.77 0.35~1.70 0.510 仅抗凝 1.18 0.35~3.94 0.793 联合抗栓 1.21 0.57~2.57 0.624 表 4 CMBs数目与出血性和缺血性卒中

Table 4. The quantity of CMBs and the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke

例(%) 项目 无(115例) 轻度(28例) 中度(15例) 重度(4例) P值 出血性卒中 1(0.87) 2(7.14) 1(6.67) 2(50.00) < 0.001 缺血性卒中 1(0.87) 2(7.14) 2(13.33) 1(25.00) 0.006 总计 2(1.74) 4(14.29) 3(20.00) 3(75.00) < 0.001 -

[1] 中华医学会神经病学分会, 中华医学会神经病学分会脑血管病学组. 中国脑小血管病诊治共识[J]. 中华神经科杂志, 2015, 48(10): 838-844. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7876.2015.10.004

[2] Charidimou A, Shams S, Romero JR, et al. Clinical significance of cerebral microbleeds on MRI: A comprehensive meta-analysis of risk of intracerebral hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, mortality, and dementia in cohort studies(v1)[J]. Int J Stroke, 2018, 13(5): 454-468. doi: 10.1177/1747493017751931

[3] Hirokazu B, Reiko S, Takuya Y, et al. Microbleeds are associated with subsequent hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke in healthy elderly individuals[J]. Stroke, 2011, 42(7): 1867-1871. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601922

[4] Puy L, Pasi M, Rodrigues M, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: from depiction to interpretation[J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2021.

[5] Andreas C, Toshio I, Solene M, et al. Brain hemorrhage recurrence, small vessel disease type, and cerebral microbleeds: A meta-analysis[J]. Neurology, 2017, 89(8): 820-829. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004259

[6] Uemura Y, Shibata R, Imai R, et al. Clinical impacts of cerebral microbleeds in patients with established coronary artery disease[J]. J Hypertens, 2021, 39(2): 259-265. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002615

[7] 中华医学会神经病学分会, 中华医学会神经病学分会脑血管病学组. 中国各类主要脑血管病诊断要点2019[J]. 中华神经科杂志, 2019, 52(9): 710-715.

[8] Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2009, 150(9): 604-612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

[9] Gregoire SM, Chaudhary UJ, Brown MM, et al. The Microbleed Anatomical Rating Scale(MARS): reliability of a tool to map brain microbleeds[J]. Neurology, 2009, 73(21): 1759-1766. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34a7d

[10] Low A, Mak E, Rowe JB, et al. Inflammation and cerebral small vessel disease: A systematic review[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2019, 53: 100916. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100916

[11] 魏宇淼, 余刘玉. 冠心病管理新理念与策略[J]. 临床心血管病杂志, 2020, 36(7): 591-593. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-LCXB202007002.htm

[12] Apostolaki-Hansson T, Ullberg T, Pihlsgård M, et al. Prognosis of Intracerebral Hemorrhage Related to Antithrombotic Use: An Observational Study From the Swedish Stroke Register(Riksstroke)[J]. Stroke, 2021, 52(3): 966-974. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030930

[13] Wilson D, Ambler G, Shakeshaft C, et al. Cerebral microbleeds and intracranial haemorrhage risk in patients anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation after acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack(CROMIS-2): a multicentre observational cohort study[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2018, 17(6): 539-547. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30145-5

[14] Wilson D, Charidimou A, Ambler G, et al. Recurrent stroke risk and cerebral microbleed burden in ischemic stroke and TIA: A meta-analysis[J]. Neurology, 2016, 87(14): 1501-1510. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003183

[15] Wach-Klink A, Iżycka-Świeszewska E, Kozera G, et al. Cerebral microbleeds in neurological practice: concepts, diagnostics and clinical aspects[J]. Neurol Neurochir Pol, 2021, 55(5): 450-461. doi: 10.5603/PJNNS.a2021.0058

[16] Shuaib A, Akhtar N, Kamran S, et al. Management of Cerebral Microbleeds in Clinical Practice[J]. Transl Stroke Res, 2019, 10(5): 449-457. doi: 10.1007/s12975-018-0678-z

[17] Parker WA, Storey RF. Antithrombotic therapy for patients with chronic coronary syndromes[J]. Heart, 2021, 107(11): 925-933. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-316914

[18] Tsivgoulis G, Zand R, Katsanos AH, et al. Risk of Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage After Intravenous Thrombolysis in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke and High Cerebral Microbleed Burden: A Meta-analysis[J]. JAMA Neurol, 2016, 73(6): 675-683. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0292

[19] Charidimou A, Turc G, Oppenheim C, et al. Microbleeds, Cerebral Hemorrhage, and Functional Outcome After Stroke Thrombolysis[J]. Stroke, 2017, 48(8): 2084-2090. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.012992

[20] Wang HL, Zhang CL, Qiu YM, et al. Dysfunction of the Blood-brain Barrier in Cerebral Microbleeds: from Bedside to Bench[J]. Aging Dis, 2021, 12(8): 1898-1919. doi: 10.14336/AD.2021.0514

-

下载:

下载: